On Oct. 28, 2011, the Court of First Instance in Amsterdam delivered its full judgment in the case of Willem Holleeder v. IDTV (verdict here, in Dutch). The judgment contains important guidelines for makers of historical movies (or other works of art) that mix fact and fiction. The court also confirms the principles laid down in the recent ECHR Mosley ruling.

On Oct. 28, 2011, the Court of First Instance in Amsterdam delivered its full judgment in the case of Willem Holleeder v. IDTV (verdict here, in Dutch). The judgment contains important guidelines for makers of historical movies (or other works of art) that mix fact and fiction. The court also confirms the principles laid down in the recent ECHR Mosley ruling.

The facts

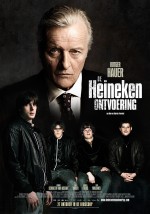

In 1983, Dutch beer tycoon Freddy Heineken and his chauffeur Doderer were kidnapped by a group of five men, among whom the claimant in this case, Willem Holleeder. After having been locked for three weeks in two damp cells, without heating and chained to the wall, Heineken and Doderer were freed by the police. The kidnappers escaped with EURO 13.6 million ransom money, but were eventually caught and convicted. These dramatic events are the basis of the movie “De Heineken Ontvoering” (The Heineken Kidnapping), starring Rutger Hauer as Alfred Heineken and produced by IDTV, which was planned for release on Oct. 27, 2011 in The Netherlands.

The movie does not claim to be a reconstruction of what happened. A disclaimer appears before the start of the actual movie, which reads:

“This movie is a cinematographic interpretation of the 1983 kidnapping of Alfred Heineken and does not aim to document what actually happened. Facts are mixed with fiction. The characters that appear in this movie are also to a large extent based on fiction.”

Holleeder is not, in fact, a named character in the movie. In the group of kidnappers in the movie, a character called “Rem Hubrechts” appears. His character development in the movie is based on elements of Holleeder and one of the other kidnappers, sprinkled with a liberal dose of fiction. Willem Holleeder, dubbed “The Nose” in Dutch media, did not just become a public figure through the kidnapping, for which he was sentenced to 11 years in 1986. He is currently serving a new nine-year sentence in an unrelated extortion case and is generally seen as the most infamous criminal in The Netherlands.

Holleeder started summary proceedings against IDTV, the producer of the movie, from his cell in the high-security prison. He asked for an injunction banning the release of the movie and, alternatively, demanded a private pre-screening of the movie to enable him to check it for ‘harmful content’. He based his claims on a violation of the right to privacy (art. 8 ECHR) and a violation of his image rights. The latter because the character ‘Rem’ is (partly) modeled after him in terms of his actions, but also because the actor who plays Rem and Holleeder look alike physically.

Artistic freedom v. right to privacy

The Court first establishes that both parties agree the public may associate Rem with Holleeder. The Court considers that Holleeder’s demands infringe on the right to freedom of expression (art. 10 ECHR), which encompasses the right to artistic expression. Also, his demand for a pre-screening encroaches on the prohibition of censorship, as enshrined in the Dutch Constitution. In effect, the Court finds Holleeder’s demands would amount to censorship.

The right to privacy may limit the right to free speech. However, as the European Court of Human Rights determined, the right to privacy does not encompass a right to prior notification of content that may harm someone’s privacy (ECHR 10 May 2011, 48009/08, Mosley v. UK). Whether or not an expression is lawful can in principle be determined only after publication.

With respect to the Heineken movie, the Court finds no facts or circumstances which would result in an exception to this principle. At the hearing, counsel acting for Holleeder had highlighted several scenes in the movie which Holleeder considered defamatory. They had not yet seen the movie (it was only shown to limited audiences before its nationwide opening) but had come across these scenes in the trailer and in a script of the movie which, as the Court formulates it, “counsel for Holleeder found on her desk” (par 3.2).

The Court concludes that on the basis of what is known so far of the contents of the movie, the movie is not unlawful to the extent that it would justify encroaching on the freedom of expression and the prohibition of censorship. The Heineken kidnapping was a major event in Dutch history and shocked Dutch society. Art. 10 ECHR protects the public interest which is served by making a movie about the kidnapping. The fact that Holleeder participated in the kidnapping ensures that any movie about it will somehow be connected to him. That does not make such a movie unlawful.

The core consideration of the court is as follows:

“The maker of a movie about a historical event is, in principle, free to add new, fictitious elements to his depiction of this event. He is also free to use actors who show a certain likeness to persons who were actually involved in the event depicted in the movie. (…) This freedom, however, is limited by the interest of someone who was involved in the actual event to not be linked with such fictitious elements.”

With respect to the Heineken movie, the Court finds that the boundaries of the freedom of expression were not crossed. IDTV made sufficiently clear that the movie is a mix of fact and fiction.

Image rights

Holleeder also argued that the film makers violated his image rights. On this ground, he demanded a complete stop on the use of his ‘image’ (i.e. the image of the actor playing the fictitious character ‘Rem’) in the movie as well as in advertisements for and on the website of the movie. The Court finds that it will be clear to the movie-going public that the person behind the character Rem is actually an actor, and not mr. Holleeder. This is especially so given the fact that the events in question occurred almost 20 years ago and that it is not unusual for actors in movies based on historical events to show similarities to the persons they are modeled after. The character Rem, as a result, is not a portrait of Holleeder.

Conclusion

The movie was released on October 27 as planned, as the Court had already rendered a dressed down version of its judgment on Oct. 21. As is common in urgent cases, the motivation of the judge followed a week later. The judgment is good news for filmmakers who aim to make a historical or biographical movie: they are given considerable leeway to add fictional elements and do not have to seek explicit approval of the people they want to depict before the movie is released. The court appreciated the strong chilling effect that would occur if prior notification would be imposed. That chilling effect is especially strong where it involves the depiction of a true crime. Obviously film makers will think again if basing a film on a true crime would force them to ask for the input of the criminals involved.

Here and here is some international news reporting on the case. Here is a news item on the case on BBC news in relation to the release from prison of Willem Holleeder.

Movie producer IDTV was represented by Kennedy Van der Laan’s Jens van den Brink